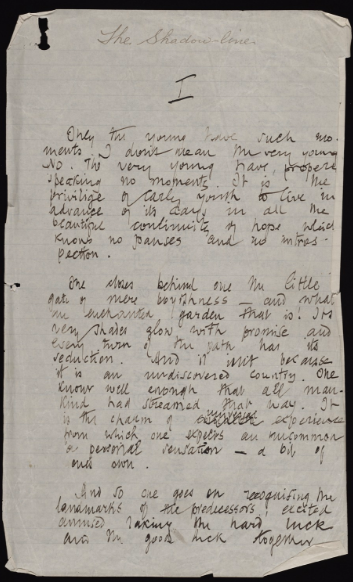

The Shadow-Line earned wide acclaim when it was published – though one critic said it was “scarcely one of Conrad’s big achievements.” That judgment aligned with the Achievement-and-Decline view of Conrad’s career. Yet the book’s brooding and ominous mood is now considered to be Conrad’s sustained response to the Great War, and the cultural climate it created in Britain. It is considered by many a gem among his later works.

The Shadow-Line earned wide acclaim when it was published – though one critic said it was “scarcely one of Conrad’s big achievements.” That judgment aligned with the Achievement-and-Decline view of Conrad’s career. Yet the book’s brooding and ominous mood is now considered to be Conrad’s sustained response to the Great War, and the cultural climate it created in Britain. It is considered by many a gem among his later works.

A sampling from the many reviews at the time of its publication in 1917:

Mr. Conrad’s “confession” is based, we are to suppose, upon some episode of his early experience – how closely must be, as always, a matter for rather tantalizing surmise. Some analogous incident lies, it is clear, in his memory, and interests him in retrospect not only for its own sake but because he sees it as typical of what in some form is bound to happen to every man.

– “Three Ages of Youth,” The Nation, 28 June 1917

The almost uncanny power of description which is revealed in all of Joseph Conrad’s books invests his new novel, The Shadow-Line, with an atmosphere of awe and mystery. It holds the reader under a spell so strong that the book must be finished at one sitting, and even when it is laid aside it keeps its grip on the memory, and the impression left remains with curious persistence.

– “Joseph Conrad’s New Book,” The Argus, 29 June 1917

For in the era of steam and electricity men have neither time nor patience for quests. As though great experiences were so much merchandise, if the one desired be not immediately at hand we take a substitute and go our way, ignorant of lack. And as for absorbing passions, we distrust them to the point of erecting a barrier betwixt us and them, and labelling our own field “sanity,” and the mysterious land beyond, first “eccentricity” and then “delusion.” …

About The Shadow-Line there is an extraordinary atmosphere of beauty. Not merely in its verbal descriptions of the “gorgeous and barren sea,” or of the ship which, “clothed in canvas to her very trucks … seemed to stand as motionless as a model ship set on the gleams and shadows of polished marble,” though not even in “Youth has the author dipped his pen in whiter magic. It is a beauty deeper than mere words go. Though Mr. Conrad’s work has always run the feeling that however much his favourite virtue, fidelity, may profit a man’s soul, his earthly existence is largely the sport of circumstances. Over and over again his heroes go down into the darkness after a losing fight with villainy or stupidity or mere inertia – dauntless and gallant figures who leave but a name behind to drift upon the light and treacherous airs about obscure gulfs and headlands until in, as it were, some breathless calm, even the name sinks into the forgetful sea.

But in The Shadow Line this is not the case. Now and then there is struck a tense note of foreboding, but the anticipated blow never falls. It is as though the gods of disaster are disarmed for once by the youth and courage shining beneath their hand. So, a beauty of human flesh and blood facing triumphantly, if momentarily, the eternal forces of the universe is in the book; the beauty of pause, as though its handful of characters were lifted for an instant and held between heaven and earth as in a crystal sphere; a beauty of independence, of isolation, and accomplishment. There is something complete, something almost sculptural, about it.

– “A Conrad Hero’s Quest for Truth,” The New York Times Review of Books, 22 April, 1917

The whole thing makes quite a short story, but in it are half a dozen pictures of sailormen, each so sharp and memorable as to make us feel we have lived with them.

– Arthur Stanley Wallace, “A New Tale by Mr. Conrad,” The Manchester Guardian, 19 March, 1917

But does Mr. Conrad intend his readers to include his story in the category of “Ghost”? Probably not. If anything, its spectrality has proved an encumbrance, involving without really enriching the issue. That evil phantasm even at its most appalling (and yet tangible) onset is nothing more than Mr. Burns nocturnally wandering on all fours; and it is against the powers of tropical rather than of spiritual distress, the perils of a crew too few than one too many, that his hero makes good. … The serene assurance of the imagination which is the outcome of all the finest work of Mr. Conrad’s genius is here broken and uncertain. The moral over-balances the story. That deepest meaning which haunts the solemn beauty he has created, simply because, it may be, it has been pursued too consciously or too familiarly, has all but eluded him.

– Walter de la Mare, The Times Literary Supplement, 22 March 1917

Mr. Conrad is an expert in the business of suggesting mystery and the action of malevolent agencies and the endurance of man under the buffets of fate. Not even Coleridge has held passers-by more spellbound under a tale of horrors on the ocean than does Mr. Conrad in this work.

– “Conrad and Others,” The Sunday Times, 1 April 1917

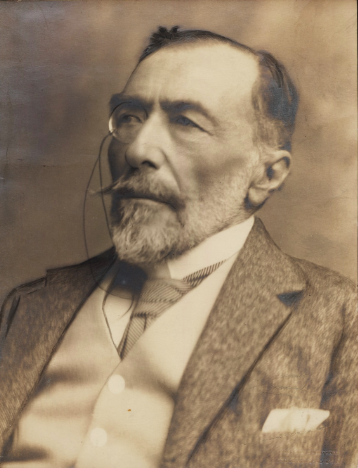

To call an artist “great” nowadays has ceased to be a compliment. There are so many of them, for one thing. And the word has become so much a euphemism of noise, bulk, show, and brag that to call a mere artists great is something like admiring a mere frog because he has blown himself out to ten times his size. And so when we call Mr. Conrad “great,” it is in the antiquated sense of the word, in the sense that we speak of “the great masters.” For that is really the only possible way to look at him; nor is it a labored truism to point it out. Criticism is so delivered over to indiscriminate praise that when a genuine master of literature swims into our ken, there is nothing left but to repeat more hoarsely and more stridently the appreciations we have devoted to not a few of his contemporaries. The utmost we can do is to think of him as a tall man looking over the heads of his fellows. We are unable to conceive him as a pilgrim in the remote and lonely tradition of art, as striding with one step from the past into posterity, and making a brief, towering angle, like Gulliver, over the confused heads of early twentieth century Englishmen.

But that is how we must try and think of him, because it is his due. It is childish to regard him as a brilliant teller of sea-stories, to point out what an oddity it is for a Pole to use the English language with such rich felicity. Until we recognize once and for all that Mr. Conrad is an artist of creative imagination, one of the great ones, not of the present, but of the world, critical words are wasted on him. …

So lengthy an introduction would be even more tedious were not “The Shadow Line,” to our mind, written at Mr. Conrad’s fullest imaginative stretch. The tale, at first glance, is almost disconcertingly bare and unambitious. … The first thing that strikes you is Mr. Conrad’s elfin power of mingling the natural with the supernatural. All the events that happen upon the voyage that is to say – the first mate’s obsession of his former captain’s dark intent to destroy the ship, the gradual spreading of tropical fever to all the gallant crew, the constant trifling of the winds with the ship in deceptive breezes, the discovery and remorse of the captain that some noxious thing has been substituted for the quinine, the heroic bearing of the steward, the descent of a darkness and silence at night upon the ship like the darkness of primeval chaos, the sick mate crawling up on deck to cast a last defiance at the dead skipper, the final exorcism of the spell and the sailing of the ship by the captain and the steward back to port – all these suggestions, experiences, and episodes might be ascribed equally to natural or supernatural causes. The artist reserves his judgment and we reserve ours.

– “The Great Conrad,” The Nation, 24 March 1917